After it was discovered during World War One, eminent scholars thought "Archaic Mark" was first-rate evidence establishing the validity of the Critical Text of the Greek New Testament. By 2009 laboratory analysis had proved that it was a 19th-century counterfeit. But today many textbooks and academic websites still cite “Archaic Mark” as valid evidence. Christians must exercise discernment – especially when the issue is the authenticity of the Word of God.

Click here to download a printable PDF transcript

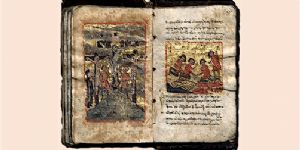

Minuscule 2427, also known as “Archaic Mark”, is a small codex (bound book) written on parchment and containing only the Gospel of Mark. It was discovered in Athens among the possessions of Greek antiquities collector Ioannis Askitopoulos after his death in 1918. In 1938 the University of Chicago acquired it from his family for its Goodspeed Manuscript Collection. [1]

Minuscule 2427, also known as “Archaic Mark”, is a small codex (bound book) written on parchment and containing only the Gospel of Mark. It was discovered in Athens among the possessions of Greek antiquities collector Ioannis Askitopoulos after his death in 1918. In 1938 the University of Chicago acquired it from his family for its Goodspeed Manuscript Collection. [1]

“Archaic Mark” is written in minuscules (lower case Greek letters) on forty-four parchment leaves and contains sixteen hand-painted color illustrations. The number 2427 refers to its designation in the Gregory-Aland numbering system used by the Institute for New Testament Textual Research in Muenster, Germany for cataloging New Testament manuscripts.

Academia Deceived

Ernest Cadman Colwell of the University of Chicago, an unbeliever who was nevertheless considered one of the world’s leading experts on New Testament Greek manuscripts, stated that he found an extraordinary degree of similarity between Minuscule 2427 and Codex Vaticanus, a major source used in creating the Critical Text (more below). Colwell asserted that Minuscule 2427 preserved a "primitive [i.e., very early] text" of the Gospel of Mark. [2] Colwell was the first to refer to Minuscule 2427 as “Archaic Mark”.

German manuscript expert Kurt Aland, scholar at the University of Muenster and a minister of the liberal German United Protestant churches, designated “Archaic Mark” as a Category 1 manuscript, asserting that it was produced in the middle of the 14th century. Aland defined Category 1 as "Manuscripts of a very special quality which should always be considered in establishing the original text (e.g., the Alexandrian text belongs here)." [3]

The “Alexandrian text” comprises the relative handful of Greek manuscripts that have been used to create the Critical Text which has been the source for the vast majority of Bible translations from the late 19th century to the present. The Critical Text, also known today as the Nestle-Aland or United Bible Societies Text, is the eclectic creation of liberal scholars beginning with B. F. Westcott and J. F. A. Hort in the 19th century, and bears no direct resemblance to any known Greek New Testament manuscript.

The 27th edition of the Critical Text, released in 1993 and used for decades as the major source for Bible translations worldwide, included hundreds of citations of Minuscule 2427 as a source for word choices. The editorial committee that controlled the Critical Text at the time consisted of Kurt Aland and his wife Barbara (professor of church history and New Testament research at Muenster); Johannes Karavidopoulos (Greek Orthodox professor of New Testament interpretation at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki); Archbishop Carlo Maria Martini (Jesuit Roman Catholic who was nearly elected Pope in 2005); and Bruce M. Metzger (liberal Presbyterian scholar at Princeton Theological Seminary). [4] There was not a single regenerated believer in Christ among them, and none believed in the divine inspiration or providential preservation of the Biblical text.

A Counterfeit Exposed – But the “Experts” Press On

Although some scholars expressed doubt about the authenticity of “Archaic Mark” as early as the 1940s, [5] religious academia generally continued to place great faith in it as an exemplar of the text of the New Testament said to date from around the year 1350.

However, in 1989 researchers found that the color illustrations in the manuscript included the pigment formula known as Prussian Blue, which was not invented until the 1700s and did not come into common use until the 19th century. Some scholars speculated that the Prussian blue pigments were the result of later retouching of the illustrations contained in the manuscript, but in 2009 tests using infrared microspectroscopy revealed that Prussian Blue was used at the time the “Archaic Mark” illustrations were first painted. [6] Some scholars speculated that the text is still “archaic” but the illustrations were added later. But the notion that space was left for these illustrations in a 14th-century manuscript but they were not added until five hundred years later defies reason.

Further, manuscriptologists have noted that it is highly unusual to find a 14th-century bound parchment volume containing only a single book of the New Testament. It is far more common to find bound volumes (codices), for example, of all four Gospels.

Additionally, manuscript scholars have found that the exemplar from which “Archaic Mark” was copied is not archaic; it contains idiosyncratic readings linking it to a revised edition of the Greek New Testament produced by Philipp Buttman in 1860. [7] Buttman’s work was in turn based on an edition of Codex Vaticanus produced by Jesuit Roman Catholic cardinal Angelo Mai (1782-1854) in 1838 but not published until after his death. Mai’s New Testament is known to be a poor copy of Vaticanus [8]. “Archaic Mark” repeats many of its characteristic errors.

Despite clear evidence to the contrary, many in academia continue to cite “Archaic Mark” as a credible source for the text of the Greek New Testament. In some cases, this appears to be the result of ignorance of the facts or reliance on academic works produced before “Archaic Mark” was conclusively proved to be a fake. But in other cases, scholars simply choose to ignore or suppress the evidence because it disagrees with their naturalistic presuppositions regarding the origin of the New Testament text.

Lessons to be Learned

What can we learn from the history of “Archaic Mark”? The most respected people in unbelieving religious academia can be fooled. Due respect should be given to genuine scholarship, but scholars can be wrong. Generally speaking, when it comes to the authenticity of Scripture, unbelieving scholars will be wrong. Those who seek to discredit the authentic text of the Bible are constantly drawn to the inauthentic by “all that is in the world — the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life” (1 John 2:16). They are far too often misled by what they wish to believe, the evidence notwithstanding. Long-held but fallacious theories die hard; they are often repeated as fact long after the evidence has disproved them.

Well-meaning Christians can easily fall into the same traps. We must exercise discernment, especially when the subject is the authenticity of the Word of God. We need to be careful when using and citing older publications dealing with the Biblical manuscripts that may not reflect the most recent truthful findings. We must beware of people and publications whose pronouncements undermine confidence in Authentic Scripture. "Beloved, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits, whether they are of God; because many false prophets have gone out into the world" (1 John 4:1). But the authentic Word of the Lord endures forever (1 Peter 1:25).

References:

- University of Chicago Library, Goodspeed Manuscript Collection, Ms. 972, New Testament. Gospels. Mark (Archaic Mark). Greg. 2427. Accessed September 2025 at https://goodspeed.lib.uchicago.edu/ms/index.php?doc=0972&obj=001

- E. C. Colwell, "An Ancient Text of the Gospel of Mark", The Emory University Quarterly (1945, Number 1), pages 65-75.

- Kurt and Barbara Aland, Der Text des Neuen Testaments: Einführung in die Wissenschaftlichen Ausgaben Sowie in Theorie und Praxis der Modernen Textkritik [The Text of the New Testament: Introduction to the Scientific Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism] (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelges, 1981), page 106.

- Novum Testamentum Graece [The New Testament in Greek], 27th revised edition (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft [German Bible Society], 1993). References to Minuscule 2427 were removed from the 28th revised edition published in 2012.

- Stephen C. Carlson, "Archaic Mark" (MS 2427) and the Finding of a Manuscript Fake, Society of Biblical Literature Forum, 2006, as accessed at https://www.academia.edu/9805089/_Archaic_Mark_MS_2427_and_the_Finding_of_a_Manuscript_Fake

- Mary Virginia Orna, Robert Nelson, et al., "Applications of Infrared Microspectroscopy to Art Historical Questions about Medieval Manuscripts," Advances in Chemistry 4 (1988): pages 270-288.

- Carlson, "Archaic Mark".

- Benedetto Prina, Biography of Cardinal Angelo Mai, Published on the Occasion of the 1st Centenary Celebrated in Bergamo on 7 March 1882 (in Italian). (Bergamo: Gaffuri e Gatti, 1882).

04-0001